What is a Mitrofanoff Procedure, and is it Worth it?

Many people who live with a spinal cord injury (SCI) experience difficulties when trying to catheterize themselves independently the traditional way, often facing several challenges with both in and out (intermittent catheterization) and indwelling catheters. I found indwelling catheters painful, and they never worked properly for me. Instead, I did intermittent catheterizations with the help of caregivers, but this process significantly decreased my freedom and independence. It may surprise you, as it did me, but there are more options for catheterization than the ones I mentioned above. One of which is referred to as a Mitrofanoff channel.

This blog will introduce you to this option by first explaining the general medical information about the Mitrofanoff channel. Next, I will take you on a journey through my experience with the Mitrofanoff channel, and lastly, I will tell you whether getting this procedure is worth it. I understand this blog may be longer than your typical blog post, but I wanted to create a one-stop-shop that discussed all things Mitrofanoff related. I sincerely hope it helps you in your decision to begin your Mitrofanoff channel journey!

Medical Disclaimer: The information in this blog is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Therefore, it is important that you consult your doctor and urologist if you are seeking medical advice, diagnostics, or treatment.

General medical onformation about the Mitrofanoff catheter

What is a Mitrofanoff catheter?

In 1980, the Mitrofanoff operation became another option for emptying one’s bladder using intermittent catheterization. This major abdominal procedure involves a urologist building a self-sealing channel from the bladder to the surface of the abdomen. Therefore, it provides an easily catheterizeable channel that has demonstrated a successful lifetime use with minimal complications. The Mitrofanoff procedure is often done in combination with an enterocystoplasty (bladder augmentation) to make the bladder larger. Enlarging the bladder is done to offer better urine storage and emptying.

How is the Mitrofanoff procedure done?

The Mitrofanoff procedure involves creating a small tube (also known as a conduit or channel) between the bladder and abdomen. Surgeons commonly use the appendix or part of the small bowel (ileum) to create this channel. Surgeons have used other internal bodily materials to create the Mitrofanoff channel, but these often result in a higher complication rate than the appendix and small bowel.

To complete the Mitrofanoff procedure, the surgeon will:

- Create a midline incision in one’s lower abdomen for entry to the bladder and appendix or small bowel.

- The surgeon will then disconnect the appendix or cut a piece of the small bowel and pass a catheter through the bowel or appendix channel to guarantee it is catheterizeable.

- Next, the surgeon will tunnel one end into the bladder through a small submucosal anti-reflux channel and the other end into a small opening in the skin, also known as a stoma, located in the lower abdomen.

- The surgeon creates a submucosal anti-reflux valve because it works to prevent urine leakage from the Mitrofanoff channel.

There are several important things to know about the Mitrofanoff stoma. The stoma should be positioned in the lower abdomen or belly button, away from any scars. It is essential that the surgeon situate the channel at skin level and not expose it past skin level. Situating the channel to stick out beyond skin level increases the risk of bleeding when a person uses a catheter and is cosmetically unpleasant.

After the surgery, the bladder will continue to hold urine the same way it always had. The bladder will be drained every four hours by inserting a male catheter into the abdomen, going through the channel, and then into the bladder. Once the urine has finished draining, the catheter is removed from the channel, and the valve within the channel closes to prevent leakage between catheterizations.

Mitrofanoff procedure steps: pre-operative process

The pre-operative process toward getting the Mitrofanoff procedure requires:

- An appointment with your general practitioner (family doctor) to get a referral to discuss the Mitrofanoff procedure with a urologist. You may also contact a urology office directly to inquire about the procedure.

- Then you will see a multidisciplinary team of medical professionals who will discuss the Mitrofanoff procedure with you and evaluate your dexterity and health.

- A urologist will then schedule you for a urodynamics evaluation to determine your bladders traits, whether it is necessary to enlarge your bladder, and whether you are a good candidate for the surgery.

- If your bladder is too small or has an exceedingly high-pressure level, you will likely need to have your bladder enlarged for the Mitrofanoff surgery.

- The urologist must also ensure you understand all potential complications and the need for long-term follow-up.

- Mitrofanoff procedure steps: post-operative process

Mitrofanoff procedure recovery:

- Recovery will take approximately six weeks.

- Surgeons will position a capped catheter in your Mitrofanoff channel and stitch it to your abdomen, where it will stay for four to six weeks after the surgery. During this time, your channel will be healing and will not be used to drain urine.

- Surgeons will insert a suprapubic catheter during surgery so that urine can drain while your Mitrofanoff channel heals.

- Once your Mitrofanoff channel heals and proves to work correctly, the urologist will remove the suprapubic catheter.

- After removal, the opening from the suprapubic catheter will heal quickly (i.e., typically in one to two weeks), and you will be left with your Mitrofanoff channel to drain urine.

After your Mitrofanoff channel has healed, you will need to receive yearly exams so that your urologist can determine the health of your bladder and kidneys. Some of the exams you may be required to get regularly include:

- Annual cystoscopy

- Annual renal (kidney) exams

- Annual X-ray of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder

- Blood tests to determine kidney function, liver function, and electrolyte balance

It would be best to discuss whether you may require these exams, what they entail, and why they are necessary with your urologist before consenting to the procedure.

Potential Mitrofanoff complications

While the Mitrofanoff surgery can be a great catheterization option for many people living with an SCI, several complications can happen with this procedure. Complications include:

- Those associated with major abdominal surgery, such as:

- Wound infection/wound reopening/hernia (2-10%).

- Excessive bleeding (2-10%).

- Slow-moving bowels, blood clots, and complications related to the use of anaesthesia (0.4-2%).

- Those related to reconstructing the bladder, such as:

- Bowel obstruction (1.4-2%).

- Anastomotic leakage (2-10%).

- Anastomotic leakage is the leakage of nutrients from the bowels into the body.

- Enterocystoplasty rupture (2-10%).

- An enterocystoplasty rupture is the rupturing of your expanded bladder after augmentation.

- Metabolic complications (0.4-10%).

- Metabolic complications include a heightened risk of high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, etc.

- Increased risk of cancer (0.4-1%).

- Those specific to the Mitrofanoff surgery, such as:

- The channel may close or shrink to where the catheter cannot get through (0.4-2%).

- If this happens, it is an emergency and may require additional surgery.

- The channel may expand or stop self-sealing between catheterizations (2-10%).

- This situation can result in urine leaking from the stoma.

- This complication may require a minor surgery to fix, in which a bulking agent is inserted into the channel to strengthen the valve. If leakage continues, additional surgery may be needed.

- Once transferred into the Mitrofanoff channel, the bowel or appendix continues to make natural mucus. An extreme amount can and make catheterization difficult.

- If this happens, the channel may require regular irrigation, sometimes daily.

- The channel may stick outside of the stoma in the abdomen, also known as stomal prolapse.

- Like traditional catheterizations, there is an increased risk of urinary tract infections (UTI), bladder stones, and bladder cancer.

It would be best to discuss these complications with your doctor to gain a more in-depth explanation and understanding of each one.

Are you a good candidate for the Mitrofanoff procedure?

The Mitrofanoff procedure is an option for people with many different issues regarding bladder function. It has become an excellent surgical option for people living with an SCI.

If you find it difficult to catheterize yourself independently, or you experience pain during catheterizations, you are a good candidate for the Mitrofanoff procedure. The Mitrofanoff surgery has been particularly beneficial for those with female anatomy (who often find it challenging to catheterize themselves independently) and people who experience frequent and severe autonomic dysreflexia due to their bladder.

In some cases, the effects of one’s SCI will stop them from being eligible to receive the Mitrofanoff procedure. For example, suppose you cannot regularly (every four hours) catheterize yourself through the Mitrofanoff channel or guide someone else to assist you in doing so. In that case, it is not a good alternative for you.

Your bladder traits will also dictate your eligibility for this procedure. The procedure works best for those with a low-pressure bladder that can hold large amounts of urine without leaking or backing up into the kidneys. However, in some cases, if your bladder does not have these traits, the bladder can be enlarged using a piece of the small bowel.

If you no longer have an appendix to use, your bowels may also impact your ability to receive the procedure. A history of inflammatory bowel disease can threaten the likelihood of long-term success of the Mitrofanoff channels functioning.

Additionally, the body is doing a large amount of healing for the first two years after an SCI. Therefore, to ensure the Mitrofanoff procedure is a good fit, most people must wait at least one year after their injury to be considered eligible for the surgery.

Obesity can make completing the Mitrofanoff procedure more difficult and decrease the procedure’s success rate. This issue is due to the channel not being able to be made long enough to reach from the bladder to the abdominal wall. Therefore, obesity may result in a patient being ineligible for the procedure.

Finally, if you plan to become pregnant in the future, you are still eligible for the Mitrofanoff procedure. However, you should work closely with your doctor and urologist to make sure your Mitrofanoff channel continues to function properly as the fetus develops. Both C-section and natural birth are still options after getting the Mitrofanoff procedure.

My experience

Why did I choose to have the Mitrofanoff procedure?

I first heard about the Mitrofanoff procedure when I was 16. I was still newly injured and just left the pediatric intensive care unit when one of my nurses arranged a meeting between me and another young woman living with an SCI. She had the Mitrofanoff surgery and was open to showing me how it worked and looked. However, she informed me that you could no longer have children after having the procedure. As a young 16-year-old who always wanted children, I decided it was not for me.

Still, after two years of doing in and out catheterizations with the help of a caregiver and no success using indwelling catheters, I was beginning to be interested in what the procedure could do for my independence. So, I began investigating whether I could still have children and scheduled an appointment with a urologist specializing in the Mitrofanoff procedure. I found out that children would still be an option for me, that I would be able to do catheterizations in my chair, and that I may independently catheterize myself. This potential level of independence made going through with the procedure worth the risks involved, and that is why I chose to go forward with the procedure.

The questions I had about the Mitrofanoff surgery

I had many questions going into my first meeting with my urologist. I wanted to know:

- Can I still have children after getting the procedure?

- What are the risks of getting the procedure?

- How long the surgery would take.

- What the typical post-operative healing looks like.

- How skilled and experienced my urologist was in doing the Mitrofanoff procedure.

- What would catheterizations look like after getting the procedure?

- Could I choose where the stoma would be positioned on my lower abdomen?

- How the procedure works.

If I am honest, I did not ask many of my questions and do not think my urologist fully informed me of all the potential risks involved. I was 18 and just excited about the potential to catheterize myself. Therefore, I recommend that you ask every question you can think of during the pre-operative discussions and testing to make a fully informed decision.

My pre-operative experience

My pre-operative experience took approximately one year from requesting my first appointment with my urologist to when I finally got in to have my surgery. I began by asking my family doctor to refer me to a urologist in the city of Saskatoon who conducts the Mitrofanoff procedure.

When I met with this urologist, we discussed the procedure, any concerns I had, how my bladder functioned and whether I had issues with urinary leakage from my urethra (i.e., from my private parts). We also talked about my level of dexterity and the subsequent tests I needed to confirm my eligibility.

My urologist then made an appointment for the pre-operative urodynamic tests. At this appointment, I received a cystometrogram, which is a test that measures my bladder’s pressure level, holding capacity, and when I begin needing to urinate. This test involved having two catheters inserted, one into my bladder and the other into my anus. They then connected electrodes to these catheters and my skin. They began filling my bladder with saline through the catheter in my bladder. A computer measured my body’s response to my bladder being filled and emptied. The testing was strange and slightly uncomfortable, but relatively quick and painless. I also had a blood test to determine my kidney function and overall health.

After this appointment, I had a second appointment with my urologist to discuss my urodynamic test results and my Mitrofanoff procedure. Testing found that I had very high-pressure levels in my bladder, and thankfully, my urologist placed me on bladder medication for the first time since my injury. I no longer had an appendix due to experiencing appendicitis at the age of 11. Therefore, we discussed how they would use my small bowel to create the Mitrofanoff channel and that due to my high bladder pressure, I would need my bladder enlarged. He explained that the bladder enlargement increased the likelihood that the procedure would be successful and reduce my chances of urinary leakage. In my case, because I did not experience urinary incontinence from my urethra, this was not an issue of concern. However, my bladder pressure could still cause leakage from the Mitrofanoff channel.

After this discussion, my urologist informed me I was approved for the surgery and asked me whether I would like to schedule the surgery. I was ecstatic, and we chose to schedule the surgery for several months after that appointment, near the end of May. Therefore, I could finish my first year of university without any concern about the surgery impacting my schooling. Then, it was just a waiting game until my surgery date came.

Finally, it was the day before my surgery:

- I had to be bathed the evening before and the morning of my surgery with a special disinfectant soap. This soap reduced the chance of bacteria on my body causing infection during or after the procedure. It did not have any scent, and I am happy to report that it did not dry out my skin.

- I was required to stop eating all food and drink only clear fluids for the day. I could continue drinking clear fluids until six hours before my surgery, aside from a small amount of water to take my morning pills.

- I had to ingest a laxative powder that evening to try and flush my bowels out for the next day. This powder has never worked well for me, so I spent the night dealing with bowel care to get my bowels moving and faced the fear of bowel incontinence when my body was not cooperating during bowel care. This situation was admittedly not fun, but it did not impact my ability to have the surgery the following day.

I arrived at the hospital, bright and early, for my Mitrofanoff procedure. I sat with a nurse for about an hour going over all the medications I take, when I take them, answering questions, and filling out the necessary paperwork. I then had my family remove all my piercings, and nurses came to assist me in getting into my hospital gown and getting transferred to a stretcher.

Very soon after, the hospital porter came to get me and brought me down to the surgery waiting room. During this time, I met my surgery team and answered the anesthesiologist’s questions. My urologist informed me I would be in surgery for approximately six hours, and then they rolled me into the operating room.

The team transferred me to the operating room, gave me anaesthesia through a needle in my hand, and I slowly drifted into a deep sleep. During this time, medical staff instructed my dad as to where he could sit to hear about my progress. My surgery started, and the wait for him began.

My post-operative experience

The first seven days

My post-operative experience started on a positive note. I woke up from the anaesthesia, and the hospital porter moved me from the observation area to the urology unit in the hospital. Due to the pain medications from surgery, I stayed very comfortable for about a day and a half after surgery. My urologist came to inform me that I was put on an antibiotic to kill the bacteria in my bladder. He also mentioned that my surgery was shorter than expected because once inside, he believed my bladder was large enough, and the augmentation was not needed.

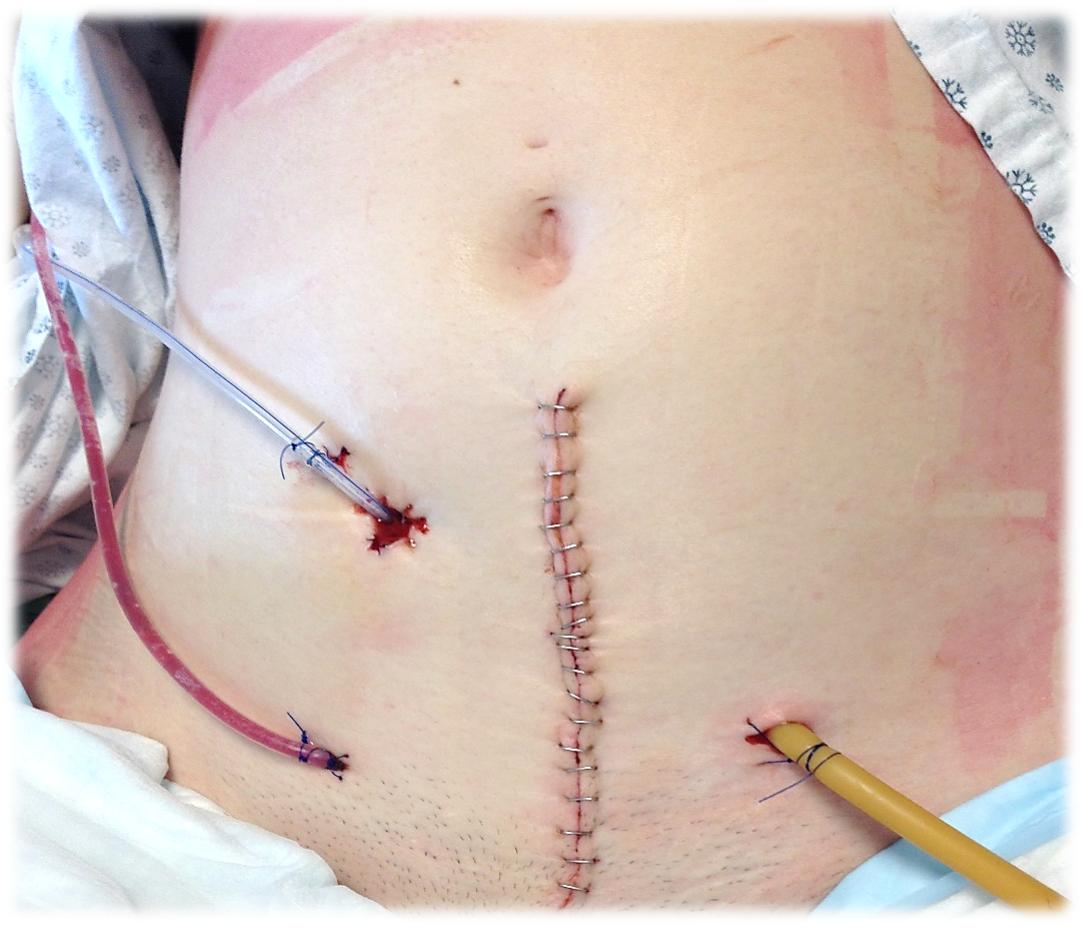

I had a suprapubic catheter in my left abdomen and a capped catheter sitting in my Mitrofanoff channel, stitched to the external stoma on my right abdomen. I also had a stapled, vertical incision in the center of my lower abdomen that was approximately four inches long and a few tubes inserted in the dermal levels of my skin to drain out common blood and fluid that forms in the skin after surgery. These are often called a Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain. As I healed, the nurses removed these JP drains.

I was only allowed clear fluids for several days after my surgery. After about three days, my medical team saw my body was handling fluids well, and I began eating soft foods. My bowels were slow but seemed to be moving, and I felt good. Therefore, after three days of handling soft foods, I was given the green light to eat regular foods again. That evening, I enjoyed two real meals for the first time in a week, including Tim Hortons chilly and a raw vegetable plate. At this point, I had all IVs removed and was set to be discharged the following day; seven days after my initial surgery. As I am about to tell you, this did not go as planned.

I woke up the following day, my discharge date, feeling violently ill. I spent the entire afternoon in bed, on my side, vomiting off and on. I began experiencing terrible pain because I could not keep my medications down, and I became extremely dehydrated. The nurses came in at around 7 pm and began trying to put my IV back in so that they could begin to rehydrate me while I continued to vomit and could not drink. After an hour of three urology department nurses and about nine needle pokes from each, and one intensive care unit nurse with one needle poke, I finally had an IV back in and started getting fluids. I continued to vomit throughout the night, while the nurses periodically attempted bowel care with no success.

The next three weeks

The next day, I was still vomiting, had not had a bowel movement, was in pain due to missing a day and a half of my regular pills, and was completely mentally and physically exhausted. That afternoon, the nurses told me we needed to insert a nasogastric (NG) tube to begin suctioning out my stomach contents and stop me from vomiting. An NG involves inserting a tube, similar to a catheter, in the nose, down the throat, and into the stomach, with the outer end taped to the patient’s nose. An NG tube may be used as a feeding tube or to suction out stomach contents.

My first NG tube was given to me when I was newly injured in the intensive care unit (ICU) and my medical team used it to feed me extra nutrients. After three days, I begged to have it taken out.

So, you can imagine I was not excited to have another one. However, this time, my medical team used the NG tube to suction out my stomach contents by attaching a vacuum to the tube. You are awake during this procedure and must drink water to help the tube down your throat into your stomach. Due to my issues with nasal swelling and bleeding, none of the nurses could insert the tube. Therefore, the ear, nose, and throat specialist came to numb my throat and insert the tube. I can tell you the spray they use to numb the area is disgusting but helpful. Also, the NG tube is one of the worst medical tools I have ever experienced thus far. Since this event, I have had one NG tube when I had my second bowel obstruction, and I now avoid them like the plague.

Nevertheless, it was nice to stop vomiting. Over the next few days, I could not eat or drink anything besides iced chips, still had not had a bowel movement, and was in excruciating pain coupled with constant autonomic dysreflexia. Doctors finally gave me an abdominal x-ray to see if something was wrong. Although they noticed what appeared to be a blockage, the nurses continued informing me that I was experiencing slow bowels. Therefore, I refused morphine because I knew narcotics slow down bowel movements. They prescribed me a medication meant to speed up my bowels, but I had an awful reaction to the medication in the form of extreme anxiety, so they discontinued using it.

Furthermore, my medical team gave me a central venous catheter (central line) due to my inability to eat or drink anything. The central line is an IV inserted into a vein within your inner right arm and threaded through the vein until it is inside the heart. After positioning the IV, they stitch it to the outer skin with ports that can have medications or nutrients injected into them. This procedure was done so that I no longer needed a standard IV for drug administration and could receive parenteral nutrition (a specialized form of food) into my vein.

After another day or two of severe pain and autonomic dysreflexia, the doctor requested that I take Morphine and Gravol to allow my body to relax and start to heal. This medication allowed me to get some sleep and relaxed my bowels enough for some poop to get through during the weekend while my doctors were away. After having my NG tube capped and with no urge to vomit, that Sunday evening, I was allowed some clear fluids.

Although I still felt something was wrong, this slight bowel movement and a small glass of tea made the doctor decide that I did not need a CT scan. I asked for it anyway, and the doctor told me to wait. An hour after the doctor left, the nurses had to connect the vacuum to my NG tube and begin suctioning again because the tea was not being digested and began making me need to vomit. Finally, the doctor sent me for a CT scan, where they saw that I had a bowel obstruction that was not correcting itself. Therefore, the following day, I went into surgery again to fix my bowel obstruction. Luckily, none of my bowels had died, and it was an easy fix.

I now had an incision that was nearly three inches longer, and I was in quite a bit of pain. Nevertheless, my bowels slowly began to move. I was eventually able to have my NG tube removed and could start eating again. Four weeks after my surgery, my urologist uncapped the catheter on my Mitrofanoff channel to ensure it drained well, and then I had my suprapubic catheter removed. This removal was slightly uncomfortable and annoying for the next several days while the opening healed and leaked excess amounts of urine. However, it healed to where it stopped leaking and was no longer an issue after about three days.

The doctor discharged me from the hospital about a week after my second surgery for my bowel obstruction and a month after my initial Mitrofanoff surgery.

Long-term experience

As of today, I have enjoyed the positives associated with a Mitrofanoff procedure and have experienced several of the possible complications. Once discharged from the hospital, I was healthy, and my Mitrofanoff channel worked perfectly. However, a month after my first bowel obstruction, I had a second. Luckily, I only required an NG tube for a few days. After a week, my obstruction had fixed itself, and I was able to go home from the hospital again.

Furthermore, after approximately 12 months, I began to have heavy leakage from the channel. First, my urologist tried switching my bladder medication twice to see if this could fix the issue, but it did not. My urologist then arranged an appointment for him to examine my bladder. He used a scope with a camera attached and inserted the scope through my urethra into my bladder. Therefore, allowing him to see what was going on inside my bladder. This procedure was quite painful, but it was cool for a student who loves medicine to see the inside of my bladder on a computer screen.

When everything appeared healthy inside my bladder, we decided to move forward with the next step and book a simple, non-invasive surgery to strengthen the valve by inserting a bulking agent into the Mitrofanoff channel. As well, Botox was injected into my bladder to relax my bladder pressure levels. I had to wear an indwelling catheter through my urethra for two weeks so that the bulking agent had time to strengthen.

Luckily, although this procedure did not stop the leaking completely, it drastically improved the leakage. Consequently, I decided that I did not want to redo the entire Mitrofanoff procedure so that the urologist could recreate the Mitrofanoff channel and add the bladder augmentation. Since Botox wears off, I need to go back every six to nine months to have the Botox injected into my bladder to keep the pressure down. While this is slightly annoying, it is a simple procedure that only requires me to be sedated rather than put to sleep under general anaesthesia. Aside from being mildly uncomfortable for a couple of days, I have no healing process after this procedure. Therefore, all in all, my long-term experience has been quite successful thus far, and I hope that continues.

How I use my Mitrofanoff channel

The process of my catheterizations through my Mitrofanoff channel is slightly different depending on whether I am sitting in my wheelchair or lying down.

When I am in my wheelchair, I have my caregiver or someone comfortable helping me complete my catheterization. I put my brakes on, and my assistant brings my shirt up and my pants and compression clothing down below my stomach. My assistant then washes their hands or wears clean gloves, opens a male, pre-lubricated, Coloplast catheter with a bag attached (Male SpeediCath), and inserts the catheter into the Mitrofanoff channel. We then both wait for the draining to finish, remove the catheter, throw it away, and rearrange my clothes back to the way they were.

When I am in bed, I do not wear any clothing that covers my stoma. Therefore, I have an assistant wash their hands or wear gloves, insert a pre-lubricated standard SpeediCath into my Mitrofanoff channel, and drain my urine into a cup. My assistant then drains the urine into a toilet and flushes it. I have also been working on finding a male catheter, with a bag attached, to catheterize myself and discard the urine independently while in bed. I do not use the SpeediCath Compact Set for this practice while I am in bed because it is not an ideal catheter for draining urine from a Mitrofanoff channel while someone is lying down.

The intermittent catheterizations from my Mitrofanoff channel are usually quick, easy, and painless. The only time I ever experience pain during intermittent catheterizations through my Mitrofanoff channel is when I have a bladder infection. Sometimes, if I really need to urinate while lying down, it can become difficult to push the catheter through the valve into the bladder. When this happens, I adjust the head of my bed, and the position change allows the catheter to pass through.

Also, when I have someone new assisting me, they are often afraid to add the minimal pressure required to pass by the valve because they are fearful when they hit resistance. Informing the person helping you that they are only hitting the valve in the channel and do not need to be concerned about adding a little more pressure often helps them do so.

Lastly, you may question why I use male catheters with my Mitrofanoff channel. I use male catheters due to the length of the channel. Some are longer than others. However, from my understanding and experience, all Mitrofanoff channels are too long to use a female catheter. Therefore, male catheters must be used with a Mitrofanoff channel, regardless of sexual identity.

The pros of having the Mitrofanoff procedure

In my opinion, there are many benefits to having the Mitrofanoff procedure:

- I can now do intermittent catheterizations without transferring onto a bed as someone with female anatomy. I also no longer need to bring my pants down to my ankles to urinate.

- Because I hardly need to undress, I can do my catheterizations almost anywhere, and I can guide any of my loved ones to assist me in doing so. Whether I am with my dad, best friend, partner, or caregiver, I can comfortably ask them to assist me and guide them through the procedure.

- Because intermittent catheters are now so easy, I do not need to use indwelling catheters when taking long trips.

- While indwelling catheters can be wonderful for many, they do not work for me.

- Now I can take trips without experiencing autonomic dysreflexia and incontinence around the catheter.

- It now takes way less time to do an intermittent catheterization.

- Including the full-lift transfer, undressing, catheterization, redressing, and transferring back to my chair, it used to take about 30 minutes to urinate.

- It now takes approximately five minutes to complete my catheterization using my Mitrofanoff channel.

Mitrofanoff procedure tips: generated from my experience

- After an SCI, wait to get the Mitrofanoff procedure until you understand the sensations in your body well, especially if you no longer have any sensation below your injury, and rely on sensations related to autonomic dysreflexia to know what is going on in your body. This understanding is essential because medical professionals often ignore us when we say we know something is not right due to the belief that all patients with an SCI have no sensation. If you believe something is wrong, do not be afraid to insist that your medical team investigate the issue using diagnostic tools. You understand your body, and you are your best advocate.

- Do not begin eating foods that are more difficult to digest until several weeks after your medical team informs you that you may return to a regular diet, especially if your team used part of your bowels to make the Mitrofanoff channel or enlarge your bladder. I recommend this because I believe one of the things contributing to my bowel obstruction was that I did not ease back into eating foods slow enough. The foods I recommend avoiding for some time after a Mitrofanoff surgery are fried foods, foods with high rates of artificial sugars, too many high fibre foods like whole grains and raw green vegetables, beans, sodas, spicy foods, and large amounts of dairy. I promise that avoiding your favourite foods for a bit longer is worth saving yourself from experiencing a bowel obstruction.

- Do not get discouraged if or when you begin experiencing complications. I know that complications can put a damper on the excitement associated with the idea of gaining more independence. However, never begin to blame yourself or regret your choice if complications arise after deciding to have the Mitrofanoff procedure. Stay positive and contact your urologist as soon as something begins to change. There are many options for revision when complications arise, and your urologist will exhaust every option for you to improve any issue. Your choice was neither right nor wrong, and complications are not your fault.

- Know a lot about autonomic dysreflexia and how to explain it to medical professionals. Although doctors and nurses should be well-versed in autonomic dysreflexia, it is my experience that many have never heard the term, let alone know what it is. Additionally, make sure you ask whether they know what you mean when you say you are experiencing autonomic dysreflexia because many nurses nod along as if they know what you mean, but they may not. I find the less alarmed they are when you mention it, the more likely they do not know what you are talking about. As patients living with an SCI, we should not need to educate medical professionals about autonomic dysreflexia. However, until the topic is part of the curriculum for all medical professionals, you or a loved one will need to educate others.

- If your medical team determines you need a bladder augmentation to enlarge its holding capacity after urodynamics testing, consider asking your urologist whether this decision may change once they begin surgery and see your bladder size. Asking these kinds of questions opens the discussion about bladder size and pressure levels, allowing you to be fully informed. This discussion also gives your urologist ample opportunity to consider both bladder size and pressure levels when deciding your need for bladder augmentation. While leaking may still happen with an augmentation, I believe that if I discussed my bladder pressure more with my urologist, he might have made a different decision regarding my augmentation during surgery.

- I highly recommend you ask your urologist whether you can choose where your stoma is positioned. Likely, you will not have a choice because it often depends on whether they use your appendix or bowel for the channel and how your organs are situated. Nevertheless, if you make it clear that you would appreciate the Mitrofanoff stoma positioned on your belly button (umbilicus), at least your medical team will know your preference. I recommend this stoma positioning because it is much easier to catheterize yourself independently for those who have less strength and dexterity. My stoma, or “little buttonhole,” as I call it, is located in my lower right abdomen. This location makes it very difficult to independently access my stoma when I am clothed and seated in my wheelchair due to the way I sit, my lack of ability to move my pants down and tuck them underneath my stereotypical “quad belly,” and my limited dexterity. Depending on my outfit, it is possible, but it is much more challenging than my friends who have their stoma located in their belly buttons.

Is the Mitrofanoff procedure worth it?

Statistically, research has demonstrated that people who have gotten the Mitrofanoff procedure believe it was worth it, regardless of the common complications they faced. However, do I believe it is worth it?

Yes, I absolutely believe getting this procedure is worth it, and I feel incredibly privileged to have the opportunity to have gotten it done. Although my friends and I have experienced challenges related to this procedure, and I continue to need regular intervention to ensure my Mitrofanoff port is working correctly, I would do it all over again. This procedure increased my quality of life exponentially, and in many ways, gave me my independence back. That, in a nutshell, is worth all the possible risks associated with the Mitrofanoff procedure.

References

Craig Hospital. (2021). Mitrofanoff procedure: Mitrofanoff procedure in adults. https://craighospital.org/resources/mitrofanoff-procedure

Barret, R., Marsden, T., & Greenwell, T.J. (2018). The mitrofanoff procedure: A continent revolution. Urology News, 22(2). https://www.urologynews.uk.com/media/15960/urojf18-mitrofanoff-update.pdf

Veeratterapillay, R., Morton, H., Thorpe, A.C., & Harding, C. (2013). Reconstructing the lower urinary tract: The mitrofanoff principle. Indian Journal of Urology, 29(4). doi: https://10.4103/0970-1591.120113. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3822348/

Bowel & Bladder Community. (2021). Suprapubic catheter. Bladder & Bowel Community. https://www.bladderandbowel.org/surgical-treatment/suprapubic-catheter/

Poncet, D., Boillot, B., Thuillier, C., Descotes, J.L., Rambeaud, J.J., Lanchon, C., Long, J.A., & Fiard, G. (2019). Long-term evaluation of mitrofanoff of continent cystostomies in adults: Results 5 years later. Advances in Urology, 29(3). doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.purol.2018.12.006